I came late to Stephen King. I’m not sure why: it’s not as if I’ve ever had anything against commercial genre fiction. What I am sure of: I’ve just discovered, however belatedly, that I get a profound kick out of his books—all of them, even the ones people tell me are generally understood to be bad. His characters are transcendently accessible. His small towns are deliciously creepy. His possessed cars and flying Coke machines and biggest fans are funny in a macabre way, and macabre in a funny way.

In addition to the novels, I’ve recently read his On Writing, after years of being commanded to do so by students and colleagues. I absolutely loved the first part, in which he (in transcendently accessible fashion) describes his authorial trajectory, from kid to teenager to man-who-threw-out-Carrie. There were many aspects of the second part—the part about the craft of writing—which made good sense, but there were a couple of others that made me balk.

Like this one here:

If possible, there should be no telephone in your writing room, certainly no TV or videogames…If there’s a window, draw the curtains or pull down the shades unless it looks out at a blank wall. For any writer…it’s wise to eliminate every possible distraction…When you write, you want to get rid of the world, do you not?

Well, no.

When I was a teenager, I had a big IKEA desk, white-topped, with fetching yellow drawers underneath. I remember getting it, in grade 7 or so. Remember setting up all my stuff in neat piles and rows, ready for a long, graceful dive into homework. Except that when it came right down to it, I belly-flopped. I fiddled with coloured pencils and rolled my desk chair back and forth, sometimes while spinning on it. I listened to the castors on the parquet floor, because that was just about the only sound in the room.

After a few weeks of this, I abandoned the desk’s vast, white, uncluttered expanse. I set myself up on my bed, cross-legged, books spread around me, radio on. This horrified my mother—and yet eventually, presented with empirical, test-results-based evidence, she had to admit that it was working for me.

I wrote Rowansong in my backyard, stretched out on a chaise lounge (in a quixotic quest to obtain a perfect, golden tan, rather than a cooked-lobster burn), or sitting on the front stoop, or at my desk in grade 9 Latin class. I wrote The Pattern Scars on the 504 Carlton streetcar every weekday morning. I wrote The Door in the Mountain in cafés and pubs; the second volume is taking shape in the very same places. I’ve only just started writing at home, and it still doesn’t feel quite right. I need distraction. Ambient noise: traffic, other people’s conversation, music, TV.

One of the things I ask students to do, in their first class with me, is answer these questions: What’s your ideal writing space? What’s your real one? The answers vary wildly, and make for thoroughly enjoyable and enlightening conversation. The upshot: there are any number of possible writing spaces. The only wrong ones are the ones that stop working for you—which is to say, the ones in which you stop working.

Another paraphrased King prescription*:

The first draft of a book—even a long one—should take no more than three months.

My first book took me six years to write. Granted, I never imagined it would be published—but it was, three years after I’d finished it. All told, a ten-year gestation period—which is, admittedly, a ridiculously long time. The first draft of the second one took about ten months; the third, two years. I truly don’t think that any of these books suffered for not having been drafted in three months. I’m a slow, careful writer who produces pretty polished first drafts—surely that counts for something? Plus, there’s life: that thing that’s happening, as you’re drafting. That thing that has jobs in it, and friends, and maybe kids, and books by people who aren’t you, and, yes, television. Should I feel guilty as I’m burning through True Detective**, because I should be writing? I’ve decided, for myself, that the answer is a resounding “no.” I’m pretty happy with the balance I mostly manage to strike, working and playing, creating and consuming. I’m okay with my 300 words a day, four days a week, because eventually, and hopefully by deadline, I’ll have a book.

Longhand or laptop? Café or white room? Music or silence? Agent or no agent? Commercial publisher or small press? Chocolate or vanilla? Like Stephen King, I’m extremely happy to tell people what works for me. Unlike him, I’m totally uncomfortable saying what should work for them.

This may be as prescriptive as I get:

If something’s not working for you, shake things up. Don’t get so fixated on routine and method, so wedded to Writing Rules imposed by self or other, that you end up wordless and guilt-ridden.

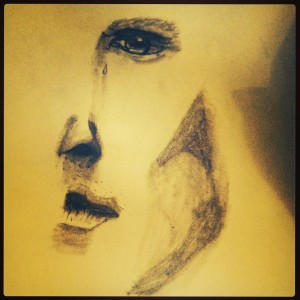

I’ll close with a mention of my Younger Daughter (who’s about to turn 12). I used to write on beds and stoops and in Latin classes; and lo, here sits YD on the bed beside me, half-watching The Simpsons, half-drawing in her sketchbook. Part of me wants to tell her to concentrate on one thing or the other, but I don’t. I figure something fairly okay will take shape on her sketchbook page. I’m not prepared for this, her depiction of a stoically weeping Benedict Cumberbatch (Cumberlock?):

Brava, distracted-yet-effective YD. Brava.

*He does say, at several points in the book, that these are recommendations, rather than rules—and yet they certainly come across as rules. Or maybe that’s just me being overly sensitive to his confident, bluff tone. I’m sometimes at ease only when I’ve prevaricated my way into an entirely new stance. (See? I just did it.)

**Oh my god, this show. It may require its own blog entry.

Recent Comments