Once, long ago (in 2001), I saw the Shire for the first time. On-screen, it was exactly as I’d always pictured it in my head: verdant and rolling, suffused in golden-green light. And when Frodo leapt up from the foot of that perfect Shire tree, he looked right too. He moved right. He and his surroundings were one big, glorious, rich, suspension-of-disbelief-inducing vision, and I gave myself to it, tearily.

Two days ago, I went back to the Shire—and it wasn’t the same.

I was aware how tenuously fresh The Hobbit was on Rotten Tomatoes, and was expecting to be underwhelmed. I did end up enjoying it. Yes, the soundtrack was relentless—but just when I’d be thinking it was too much, a leitmotif would come skirling through the noise, and then I’d think, “Ooooh, there’s the ring/Shire/Frodo/Gandalf theme!” and subside into a nostalgic haze. Yes, some of the characters’ motivations could have been more clearly set up (it wouldn’t have taken long—say, 45 seconds, which could easily have been shaved off all that underground running about on precarious goblin bridges). Yes, a couple of the dwarves (including their king) didn’t look remotely like dwarves, but like men who might have stepped up to pledge their swords to Aragorn. And yes, I missed Aragorn. But these were quibbles.

The more-than-quibble, though; the reason the Shire and all its inhabitants looked so very different: they were rendered via 3D HFR 48 frames-per-second technology. Unlike other viewers who’ve weighed in on the subject, I didn’t adjust within the first ten minutes and then surrender myself to a state of super high-def magic. Director and photographer Vincent Laforet points out that this technology might work really well with nature documentaries or football games, and I imagine this is probably true. (He points out a whole lot of other things I wholeheartedly agree with, and breaks down the technical issues in ways I almost understand.) But this is a fantasy we’re talking about. And super high-def kills fantasy.

To belabour the point: Middle Earth is not the Real World. And, totally paradoxically, the more real it looked, the more aware I was of the artifice that had gone into making it. I know that other viewers have found that the hyper-realism evoked by the HFR drew them more fully into the story, but it left me feeling awkward and impatient—as if I were watching director’s cut deleted scenes instead of the real movie. Now, to be clear: when I got the director’s cut DVDs of the other three movies, I devoured the deleted scenes and unedited footage. I found this both as intimate and as distancing as looking at an x-ray—at starkly-lit images of the bones that lay beneath the captivating, gorgeous flesh of the films. The Hobbit, though, was an endless, deleted-scene skeleton.

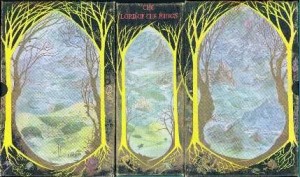

Of course, this very, very subjective response springs from my long and personal relationship with fantasy. It’s a relationship that began on the page—and the images I conjured from the words I read were all pretty fuzzy. I liked them that way. Ergo, my reactions to fantasy covers were entirely clear-cut: dream-like, impressionistic landscapes featuring distant, crumbling architecture of some sort, and maybe some shadowy human beings, were great (Mark Robertson’s Titus Groan covers, for example, or Roger Garland’s and Pauline Baynes’ Lord of the Rings ones.) Photo-realistic, close-up human beings (Darrell K. Sweet’s [no relation] on the Wheel of Time covers, say): ugh.

Roads go ever ever on

Under cloud and under star,

Yet feet that wandering have gone

Turn at last to home afar.

Eyes that fire and sword have seen

And horror in the halls of stone

Look at last on meadows green

And trees and hills they long have known.

Recent Comments