I alluded to this in a previous post.

I alluded to it in Sweden too, when many of the wonderful people we met there asked where we’d already been, and what we’d been doing. “I gave a lecture-type thing!” I’d say. “To a bunch of graduate biology students, plus members of the general public! [This thanks to Karin Pittman, charismatic biology professor and impassioned supporter of art and food and all kinds of uncharted waters. Also the companion human of a majestic Norwegian Forest Cat, plus a tabby who uses the bidet.] I had SO MUCH FUN!”

When we got home, I got a message from one of these wonderful people, who asked when that talk I’d given in Bergen would be up on my blog.

Nahal, and your martini-swigging cronies: that would be

Now.

*

Peter began by expressing his sense of insecurity about this context. I’ll do the same—because I have far more reason to feel out of my depth, here. Science and I had a very brief relationship, back in the 1980s and early 90s. I dropped biology in my second year of high school, before I got to do a single dissection, and after I graduated I moved on to a liberal arts undergraduate degree. As part of this degree I had to take a couple of credits in science—so in amongst all my Spanish literature and art history and Greek tragedy and philosophy courses, I ended up doing a whole lot of physical anthropology ones, plus a geography. Yes, I know: a geography! I was kind of proud of the way I was then able to throw around words like Kingdom Phylum Order Class, and to cite other science-y terms and concepts—but I always felt like a tourist who understands just enough of a foreign language to order beer and then ask where the bathroom is.

So science and I had a very brief academic relationship—and we also had a half-hearted but well-meaning literary one. I read some science fiction, and quite liked it—but what I read far, far more of was fantasy.

When Peter and I were Skyping with Karin about today, and I outlined what I thought I might say to all of you, her reaction went something like: “Fantasy drives me crazy! It’s always some medieval setting, and the women are all, ‘Oooh, save me’…I don’t get it, and I don’t have time for it.” She’s far from alone in this estimation of fantasy. I meet a lot of science fiction writers who think fantasy’s clichéd. In fact, my esteemed husband decided he’d mock me, when we first met, by calling me Unicorn Girl, since this just about summed up his own preconceptions about fantasy: medievalish magical beasts and schools for wizards and probably teenage girls falling passionately in love with sparkly vampires and crying a lot. Basically: a pretty superficial genre, and a static one too—stuck in a dead, long-ago past, not a vital future. (By the way, this attempt at mockery went a little bit astray, as I loved being the Unicorn Girl, and this is what he still calls me. Also, this image I sent him, back when he first mocked me, has become my phone wallpaper.)

A lot of fantasy is mindless and tired—but this is true of any genre, as science fiction author Theodore Sturgeon pointed out when he was defending his own genre against accusations of shallowness.

So today I hope to do a few things: urge those of you who share this misconception to unlearn what you’ve learned, by way of a discussion of the at times quite political roots of modern fantasy, and its continued influence in popular culture. In fact, if I may speak that vaguely foreign language of biology again, what I’m going to talk about is evolution: both of a literary genre and of myself, writing within it.

I tried to be empirical and objective, when I was coming up with a format for this talk, but it didn’t work: once a liberal arts student, always a liberal arts student. So I’m going to thank you in advance for your indulgence, and begin with:

Once upon a time, there was a little girl. Who was me.

I grew up in a family of book-lovers: my mother was a librarian, my sister ended up getting a PhD in English literature, and my father was a classics and English professor—so I kind of had no choice: stories were a staple of my life, from the beginning. Greek myths are the first ones I remember hearing.

This was myth at its purest and most elemental: told in the dark by someone with a deep, mesmerizing storytelling voice. There was such drama in these stories: fear, violence (though I realize now that my dad spared me the ickiest parts), love, betrayal, triumph and defeat. They dealt with things that the 4-year-old me was thinking about: why are there seasons? What makes thunder? Even then, I knew that the myth’s answers (Persephone’s kidnapping and Zeus’ thunderbolts, respectively) weren’t real answers—but they were so clever and so compelling that I enjoyed believing them, for as long as the stories lasted. Another wonderful thing about them was that they had a shape; they had conflict and resolution, even if the resolution wasn’t always happy, and this too was really satisfying and safe. Best of all, though, were the gods and goddesses and demi-god heroes. They were big, amazing characters who made me forget I was so small.

My father told me another, very different kind of story back then, too: the Jimmy and Louise tale. Unlike the myths, this kind was participatory. He always began like this: “Once upon a time, there were two rabbits named Jimmy and Louise. One day they decided to go for a walk. The sun was shining, the sky was blue…but then they came to a part of the woods where they’d never been before”

—and from that point on, nothing was known. I had to make it up. All I was certain of was that the stories always featured this same pair of risk-taking rabbits, and that there’d be serious danger in the woods, and/or wondrous magical stuff, and that it would all end happily ever after. So there I was, at ages four and five, making it up as I went along—taking characters and building stories around them; creating fantasy fiction before I even knew what that was.

Fairy tales featured too, not long after this—so when I started writing down my own stories, at about age seven, they almost always began “Once, a long time ago, there was a little girl who…”. The little girl was me, only cooler, in a world nothing like mine—because why put yourself in the very same world, when there were so many others you could create?

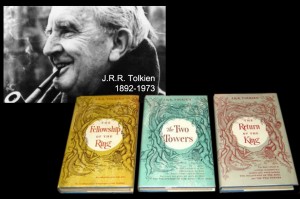

Then, on a vacation my family took when I was 14, I read Tolkien’s LoTR for the first time.

Here was the mythic structure I remembered from those bedtime stories my dad had told me, but there was also the most overwhelming sense of newness and discovery, because both the places and the people in these books were so clear to me.

So the arc of my first fiction loves was:

Greek myths, to

Fairy tales, to

Tolkien.

This is a satisfying and relevant trajectory, because it also traces the early evolution of what we now know as modern fantasy. After all, Tolkien’s intention was to create a mythology. He wrote, in a letter to a reader,

“[England] had no stories of its own, not of the quality that I sought, and found in legends of other lands.”

So he drew on the Celtic, the Roman, the Norse to craft the languages, lands and races that became his own Middle Earth mythology—but why? Why did he feel the need for a mythology in the first place? Why did he turn back instead of forward?

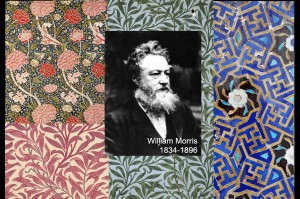

To figure this out we’ll have to go one fantasist further back—to William Morris, who was an enormous influence on Tolkien.

You might recognize Morris’ name because you know something about the Arts & Crafts movement—but very few people are aware that he wrote two novels that are considered the first works of modern fantasy. They’re quest stories, and they’re wonderful: poetic, full of vivid imagery and adventure and, yes, magic. (Incidentally, his Well at the World’s End, written in 1896, features a female character who’s the furthest thing from a damsel in distress.)

Tolkien was profoundly inspired by myth and Morris—and by the Romantic tradition. Here’s where I get to talk a little about the intersection of fantasy and science. The fantasy writers of this period espoused Romanticism—as did many of the scientists of the day. This was the “Age of Reflection,” which was a reaction against the Enlightenment and its “Cult of Reason.” In the 19th century, you had Lamarck and his “new science of biology”, Alexander von Humboldt, geographer and naturalist, Herschel, the astronomer…–all of them asserting, in their various ways, that a reliance on mechanism and what they saw as overly rational approaches to the world would lead humankind to turn away from nature—at its peril.

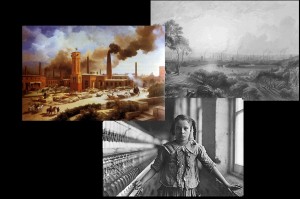

Modern fantasy was born then, a product of and reaction to the scientific tenets of its time. Romantic fantasists like Morris and Tolkien weren’t protesting the existence of technology, but the mass, dehumanizing, destructive effects of it—the workhouses full of fatally ill children, the factories that ruined the air and the countryside

—and, in Tolkien’s case, the weapons that he saw kill with an entirely new level of efficiency in the trenches of World War I.

Both of these authors could have written political treatises or newspaper columns. Instead, they chose fantasy fiction as their means of communication—because, as Peter mentioned, we’re all hardwired for story.

So what Morris and Tolkien did was draw their readers back, or sideways, into places where mortal beings, not gods, had agency, and something approaching actual personalities. Whether predestined or random, their actions had meaning in a world full of danger and uncertainty. When asked to differentiate between science and magic, modern-day science fiction author Ted Chiang responded:

Magic is, in a sense, evidence that the universe knows you’re a person. When people say that the scientific worldview implies a cold, impersonal universe, this is what they’re talking about. Magic is when the universe responds to you in a personal way.

Morris and Tolkien transformed ancient mythologies and medieval romances into something far more modern: a literature of meaningful escape in which human beings had power. No matter how important their plots were, it was the characters that drove these early modern fantasies—and this was a step in the genre’s evolution.

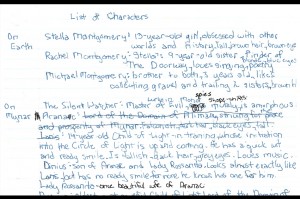

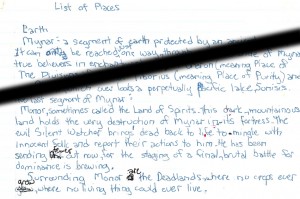

Almost immediately after I’d finished reading LotR, back on that car trip when I was 14, I started writing my very first novel, about a (surprise!) 14-year-old girl who finds the entrance to another world—a world being torn apart by Evil in the form of a malevolent character named The Silent Watcher. Here you see my original notes, describing the places and characters featured in the work.

|

|

Of course, the girl defeats The Silent Watcher, with the help of the handsome, slightly depressive young man with mysterious sea-grey eyes, and she stays, happily ever after, in this magical dragon-filled place. I should note that, even at age 14, I knew that such endings were stereotypical: what precedes this part of the sentence is:

And though I am aware that this has been said before, by many people, I will say it very quietly, in passing—all lived happily ever after.

So. Fairy tale fantasy with a Tolkien twist or two—but I was so proud of it—and I learned a lot: like, starting a story is super easy but writing the middle stuff is really painful, and not knowing exactly how it’s going to end is exciting and nerve-wracking at the same time. Though my stories’ themes and forms have changed a whole lot, my process kind of hasn’t.

Back to Karin’s “It’s all set in the Middle Ages!” We can, in fact, blame Tolkien for this common misconception—because his mash-up of mythologies was so enthralling to so many people that he became the first writer of fantastical fiction who got famous. He spawned generations of imitators: writers who wanted their own light elves and dark elves, wizards with pointy hats, beautiful princesses and quests for pretty and powerful magical objects. These later writers used his mythology but by and large didn’t transform it. I read a few books like this

—and while they satisfied me in a superficial, knowing-what-I’d-get way, they didn’t thrill me with newness, the way Tolkien had when I’d first read him. No: epic fantasy, as it’s now commonly called, no longer challenged or invigorated me.

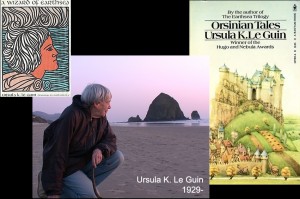

Luckily, Ursula LeGuin was waiting.

I first read her Wizard of Earthsea trilogy when I was fairly young. When I was a teenager I really discovered her—and all of a sudden I realized what truly modern genre fiction looked like. For the first time, too, I became aware of gender and genre. The goddesses of the myths my dad told me were powerful—but they were goddesses, not real women. Tolkien’s female characters with major speaking parts numbered precisely three—and they were idealized, cast in roles typical of the Romantic period—even Eowyn, who was my favourite.

LeGuin’s stories, whether written in the 60s or the 90s, were deliciously challenging—her characters grappled with hard, hard issues of identity and politics—and the language she used was beautiful and lyrical without being old-fashioned. Also, she was (and is) one of those rare authors who writes both science fiction and fantasy—and I consumed it all. This was genre fiction that was alive, right now, not generations ago; fantasy that imitated no one else’s—and I could feel it changing the way I read and the way I thought about writing. In an interview in 1982, when she was asked about how she’d come up with the idea for her novel, The Left Hand of Darkness, LeGuin responded:

[The Left Hand of Darkness began with] an image of two people (I didn’t know what sex they were) pulling a sled over a wasteland of ice. I saw them at a great distance. That image came to me while I was fiddling around at my desk the way all writers do… [My books have] all begun differently. That image from The Left Hand of Darkness is a good one to talk about, though, because it’s so clear. Angus Wilson says in Wild Garden that most of his books begin with a visual image; one of them began when he saw these two people arguing and he had to find out what they were arguing about, who they were. That fits in beautifully with the kind of visual image that started The Left Hand of Darkness. But the others have come to me totally otherwise: I get a character, I get a place, sometimes I get a relationship and have to figure out who it is that’s being related.

So she didn’t start The Left Hand of Darkness because she was determined to examine a world in which there was no gender. That came later, once she got to know the characters she’d seen in that image of the ice. Her take on characterization was compelling to me the moment I read it, in one of her books of essays. She wrote:

In many fantasy tales of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries the tension between good and evil, light and dark, is drawn absolutely clearly, as a battle, the good guys on one side and the bad guys on the other, cops and robbers, Christians and heathens, heroes and villains. In such fantasies I believe the author has tried to force reason to lead where reason cannot go, and has abandoned the faithful and frightening guide, the shadow. These are false fantasies, rationalized fantasies. They are not the real thing.

Her characters and their stories changed the way I read and the way I wrote. Instead of a Big Supernatural Evil Dude, my third novel, which I wrote when I was 17, featured a conflicted young man who makes the wrong choice for understandable reasons. All of a sudden the Light versus Darkness of my earlier writing wasn’t enough. LeGuin inspired me to write about difficult, ambiguous situations, and difficult, ambivalent characters.

A few years later, when I was an undergrad, I had two separate, simultaneous revelations: magic realism and Mervyn Peake.

A lot of papers have been written about the differences between magic realism and mainstream contemporary fantasy, but I still consider it part of the genre. In fact, it may well be the most purely fantastical of all—because it’s about the matter-of-fact co-existence of everyday things with totally impossible ones. There’s no internal logic to it, as there is in mainstream fantasy, so it’s full of strangeness and mystery and allegory. Allegory—because, like Tolkien and Morris, the magic realists were reacting against the social and political realities of their time.

In 1967, in Colombia, where two hundred thousand politically motivated murders were being committed, Gabriel Garcia Marquez wrote a book called One Hundred Years of Solitude. He wrote of a place where war and modernity co-existed with legends and magic. He used fantasy to comment on what he saw as the never-ending, vicious repetition of his country’s tragedies.

I also read Jorge Luis Borges, whose most famous works, published in the 40s and 50s, predated Marquez’s. His stories weren’t obvious political allegory—they were fables; surreal experiments in which he used symbolism and even mathematics to explore his favourite enormous themes: the nature of language, time, meaning and being.

I immersed myself in Garcia Marquez and Borges—and the fact that I read their stories in Spanish added one more layer of magic and otherness to the experience. Labyrinths, mirrors, time that folds up so that characters can imagine the past and remember the future—I was totally hooked.

And then, right around the same time, I discovered Mervyn Peake’s Gormenghast series

—three books in which the crazy, chaotic castle is as much a character as any of the eccentric human beings—and in which these characters are far, far bigger than the plot. Tolkien experienced firsthand the horrors of World War I, and Peake fought in World War II.

Rather than writing, as Tolkien did, about a world of pastoral wonders and epic quests, Peake wrote about claustrophobia, the strangle-hold of tradition, the hopelessness that was everywhere—in the world, and within Titus, the main character. Titus is not on a world-saving quest, like the hobbit Frodo; all Titus is looking for is an escape from the confines of his own life. Peake’s books are utterly modern in their unsentimental bleakness, but they’re also written in lush, poetic language that has been compared to the prose of Charles Dickens.

All of these stories—Borges and Marquez and Peake’s—had a huge influence on my first published book, which I wrote because I was sick and tired of the epic fantasy Tolkien imitators.

I gave my young female protagonist a quest that seems lofty but ends up being dark and bittersweet, not triumphant; I created a desert fortress where time has no meaning and the halls and doorways are always changing. And I created a legend, within this world, that I then tore apart and told the truth of, in the following book.

This was new ground, for me, as a writer—but the marks of fantasy’s evolution were all there.

There have been other major evolutionary stages in the genre, which I don’t have time to go into at any length—but I will mention modern retellings of fairy tales. These are books that give real flesh and motivation and backstory to characters who existed only as symbols before. Imagine the difficult, nuanced lives of the women who became the Wicked Witch or the “evil” stepsister. This is fantasy evolving, transforming, becoming more relevant by going back.

The medievalish epic has also evolved, believe it or not. George R. R. Martin’s still-being-written Song of Ice and Fire series features many of the same tropes as Tolkien’s writing did: dragons, horse lords, human tribes with their own vividly rendered gods and lands and languages. But Martin’s writing in the early 21st century, not the early 20th. There’s no chivalry in his fantasy: it’s darker, grittier, crueller than Tolkien’s. And while Tolkien did myth one better by giving his characters actual personalities, rather than shorthand traits, Martin goes further yet: he takes you inside the characters’ heads, one by one by one, rather than showing them to you from a slightly detached authorial distance.

Martin, in fact, provides a nice jumping-off point into this next and final bit, about fantasy in popular culture.

Game of Thrones, the TV show that’s being made of his epic series, has attracted zillions of viewers, many of whom haven’t read his books, and many more of whom aren’t genre fans, per se. Myths were huge in the ancient world, and they’re obviously still going strong. Asgard became Tolkien’s Valinor—and a couple of summers ago, Thor fell out of Asgard into the New Mexico desert, and millions of us watched, in movie theatres around the world.

The elves of Norse mythology become the elves of Tolkien’s Middle Earth become Orlando Bloom.

Transformation, evolution—still at work.

It’s ironic that technology is driving the meteoric rise of fantasy in popular culture. Comic books once beloved of relatively small, exclusive groups of people can now be brought to stunning, 3-D life before the eyes of everyone.

The story that Tolkien wrote as a protest against the destructive rise of technology is now playing on screens large, small and everywhere. The machines of the Industrial Revolution made Morris and Tolkien yearn for magic and innocence and escape; the Internet and blockbuster CGI tap into our yearning for the very same things. Because we do still need these stories. There’s safety in a familiar kind of escape, with our world as unstable as it is. Economies crashing; wars raging; climate changing… And the more science makes possible, the more we long for the impossible.

But myths and fantasies weren’t popular in their times only because they touched on existential social issues—no, myths have always been fun—engaging delivery platforms for more subtle messages. Wine, women and song; secret identities; shapeshifting; unintentional cannibalism; blood feuds lasting millennia—these were the pop culture entertainments of their time, from which our Avengers and Game of Thrones descended.

In terms of my own relationship with the geeky side of popular culture… I’ve already mentioned my first published book, A Telling of Stars. Back in 2002, when it was about to come out, I found myself at my first “con”–or, science fiction/fantasy convention. I’d always been an unofficial member of “geek” culture—since 1977, anyway, when I saw a brand new movie called Star Wars.

Geekdom was a field dominated by boys, back then—but I had no problem with this. I also played the trombone

—I was the only girl doing this, right up until grade 11—so I spent a lot of time with geeky boys, revelling in our weird, almost coded language. Still: when I got to my first con, decades later, it was kind of overwhelming.

Stormtroopers walking around in groups. Star Trek jerseys everywhere. Dealer rooms overflowing with Doctor Who and Lord of the Rings action figures. I kept thinking, “Oh my god, if I had been able to see all this when I was 15”–but you know, I’m kind of glad I didn’t. I had conversations then, in the back row of the orchestra—geeky but personal interactions.

I do still enjoy conventions and big-budget movies—these contexts in which people have enormous shared experiences and are more crowd than individual. But these things don’t inspire me or feed my writing. In my own work, I still crave the small, the individual, the human: character, not concept, is what I need before I can write a single word.

In the case of my recent writing, I’ve gone back to the stories my father told me in the dark, before I knew how to read. My last book, The Pattern Scars, started with a character from Greek myth: Cassandra. Poor Cassandra, cursed by Apollo to always tell the truth and never be believed. What if, I thought, there were a woman who was cursed to never tell the truth and always be believed? What would that do to her relationships with others, and herself?

And the book I’m writing right now began with the Minotaur. What if, I thought, the Minotaur were a shapeshifting boy who doesn’t get killed by the Athenian hero, Theseus, in the labyrinth—what if a young woman saved him? A sort of Bronze Age Beauty and the Beast—featuring another shapeshifting boy, Icarus, who changes into a bird, and a princess, Ariadne, who’s not the lovestruck girl of myth, but a girl who’s manipulative, bitter and sad. I’m in the middle of this one—the stage at which I have no idea what’s going to happen.

These stories have ended up being about the high price my female protagonists pay as they fight to find power and control, despite often insurmountable odds. But this theme is the effect, not the cause. I never know what’s going to happen to these characters when I’m beginning their stories. I certainly don’t know how the stories end. I don’t write up experiments I know the results of, as Peter does. I dive in blind, without a hypothesis—which is kind of appropriate, speaking of themes. Uncertainty—not knowing—lies at the root of myth, fiction, science; existence. What’s next? There’s uncertainty, and there’s the wonder that comes from guessing. Whether you find this wonder in hard science fiction stories about a possible future or fantasy stories about a possible past, it underlies everything we do and think, feel and read and write. The wonder and urgency of not knowing drives fiction, and us, to evolve.

Here, to end, are some beginnings.

What’s next?

Recent Comments